- Subscribe to my newsletter! Click here →

Sheep Camp Avalanche

When I first wrote about the Sheep Camp Avalanche of 1898, I saw it both from Liza’s perspective and Ben’s, but for continuity’s sake I kept Liza’s in the book. This version doesn’t include the moment when Ben comes upon Liza and tries to rescue Stan because most of that was blended into the ultimate chapter.

APRIL 4, 1898

APRIL 4, 1898

“Every day this place looks different,” Thompson said, standing beside Ben.

He’d been inside with most of the others, saying prayers for Palm Sunday. Ben had not attended. He hadn’t gone to even one service since they’d arrived. At first some of the others had regarded him with a vague suspicion, but no one asked why he stayed away. And he didn’t offer any explanation. The truth was he had given up on religion years before, and up here he felt no obligation to visit the church. The glory of the Yukon was all he needed.

The men were getting along well, doing the best they could in conditions that should have driven them crazy. They worked hard and made the best of the lighter moments. The other day they’d taken a bunch of illegal liquor off a group of climbers at the Pass. Following orders, they’d spilled it all onto the snow to make sure the smugglers couldn’t get it back. Later on that day, Miller had come by and shoveled a bunch of the snow into a bucket, and when it melted the Mounties had sat back to enjoy a little whisky. It had been a hard winter; their superiors either joined in or looked the other way.

“It’s … almost warm,” Ben agreed.

As if it heard, the mountain groaned.

“Keep your voice down, Turner. Sounds like it wants to keep sleeping,” Thompson mused. “I have a feeling it’d be bad to wake it up.”

“Dawson’s gonna get wiped off the earth by all this snow.”

Thompson spun towards Colonel Dempster, feigning confusion. “Say that again?”

Dempster laughed, well acquainted with Thompson’s rough teasing. William Dempster had emigrated to Canada from Wales, and he’d been with the Mounties for over ten years. He’d never quite shed his curling, sing-song accent.

“I said,” he replied very slowly, “that Dawson City will be washed away by the thaw. Did you get that, Thompson? Or shall I slow it more for ya?”

Thompson responded with a rare half smile.

“The river won’t mind moving those fancy buildings and tents one bit,” Dempster added.

“Yep. It’s past time to be tempting the mountain. Not even the local packers are working anymore.” Thompson shook his head. “Those fools on the trail, well, they think they know something the Indians don’t. Good luck to ‘em.”

Then one of the men called out. He had his binoculars out and was pointing into the distance, at the endless mountain peaks. Ben put a hand to his brow, shielding his eyes from the sun, then he pulled out his own binoculars. At first he saw nothing, then it seemed a patch of the distant snow blurred.

“Avalanche,” someone said. “It’s starting.”

The small slide shifted, reaching out and pulling in more of the mountain as it grew. Snowballs became courageous, picked up speed, grew to the size of men as they plunged down the slope, and a rumbling reached the men; the groggy voice of the waking mountain. They’d known it was imminent, but seeing such a thing was completely different from expecting it. Where the whiteness had lain soft and sparkling, now it piled high with massive lumps of rolled snow, rocks, and splintered trees. Nothing moved.

“That’s gotta be twenty feet deep,” someone marveled.

“Incredible.”

Ben thought of the Pass, of the long, straggling line of climbers. “It’s a good thing the climbers—”

“That’s coming. Don’t fool yourself.”

“Surely they’d stop after this. Wait it out until it’s safe.”

“Some might. Some might just think they’ve gone too far to turn back.”

“Can we stop them?”

“Do you really think they’d listen? Besides, where would they go?”

Two hours later the mountain could bear the weight no longer. The men were enjoying their noon meal when the rumblings they’d heard all morning were punctuated by a huge thump! then a shuddering roar so much closer than before. It drowned out their exclamations, buried the scraping of chairs as the men bolted to the door.

Seconds later they were enveloped in silence. The avalanche was over.

“God Almighty,” one of the men said. “It’s come down on Sheep Camp.”

**

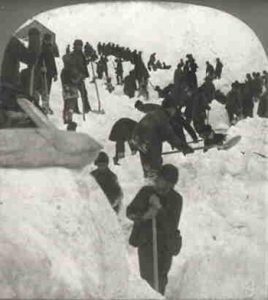

Snow fell in large, wet flakes, soaking their sleeves, dripping off their faces as they worked. It was a tricky matter, loading dogsleds and navigating towards the base of the avalanche, but there was no hesitation among the men.

As one the Mounties sped up their descent despite the constant threat that the mountain could collapse again at any moment.

Ben rushed towards a staggering man, catching him before he fell. “How many were here? Does anyone know?”

The man was thin, his bony jaw bristled black and grey. He blinked slowly at Ben through red, swollen eyes. He looked as if he couldn’t quite place where he was, so Ben gave him a little shake.

“Are you all right? Tell me how many were here!”

The survivor’s mouth opened, and a dazed light came into the man’s eyes. “Hundreds. There was hundreds of us.” He pointed a trembling finger toward the mountain. “Some hung onto the rope, but it did them no good. They’re all gone. It was … it was so fast. Wasn’t nobody could get outta the way.”

More rescuers were arriving in the dozens from below the slide, all of them carrying shovels. But where to start?

A quiet, pleading voice cut through the snow beneath them, and Ben dropped to his knees.

“Are you all right?” he yelled into the snow.

“Help me!” The voice was weak but clear.

Ben put everything he had into his shovel. “I’m almost there. Just hang on.”

Minutes later a mitt appeared, and eventually a man’s head. Ben used his fingers to strip away the snow around his face so he could breathe.

“Breathe slow,” Ben said, scraping more snow away. “Don’t cry. You need the air. It’s okay. You’ll be safe now.” He stood up, called for help, then crouched back beside the gasping man. “I’ll send someone to you,” he said.

“Don’t leave me!”

He had no choice. Every minute he spent on this man meant another person would cease to breathe. He stood and backed away, waving over a couple of men with shovels. “You have air. I have to help someone else.”

For the rest of that day and night he’d given it all he had. When his hands could no longer curl around the shovel’s handle and his knees could barely support him, Ben collapsed in a tent for a couple of hours, where he’d been plagued by nightmares. When he rose before dawn, ready to start again, he felt more exhausted than before.

The Mounties stayed at Sheep Camp for four days, helping to get the tough little camp back on its feet. On the day of the avalanche, Ben and the others dug through the night along with hundreds of volunteers, and every time a survivor struggled out of the snow the camp erupted in cheers. Ben had cheered as well, but as glad as he was to see them, his heart wasn’t fully in it. The truth was they’d been fortunate—hundreds of people had been at Sheep Camp when the mountain collapsed, and only fifty or so had been lost. But Ben couldn’t get it out of his head that those fifty dead had families. The memory that haunted him the most was of that poor young woman he’d left alone in the devastation, to mourn her lost brother

Eventually the search was called off. What frozen corpses they were able to find were loaded onto sleds and taken to a mass morgue at Skagway. More remained hidden until after the snow melted that spring, bringing the number of deaths to sixty-three. They were buried near Sheep Camp in a quiet little basin protected by the mountains. The minister held a service, observed by the prospectors still climbing the Pass, and life in the Klondike returned to normal. Summer grew from spring, bringing life to the land around the graves, and wildflowers grew on the slopes all around. The soil warmed and melted the deep layers of frost, and the little basin slowly filled with water. One day the relentless line of prospectors paused by the new lake, curious about the ripe smell rising from the water. Freed from the permafrost, sixty-three bloated corpses had risen from the depths and now floated like corks on the surface of the water.