- Subscribe to my newsletter! Click here →

Inadvertent Abandonment

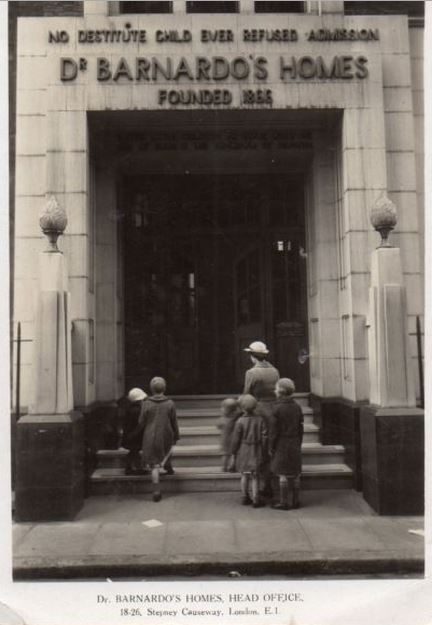

The Industrial Revolution brought tens of thousands of people from rural locations to the cities, where they were met with terrible, filthy living conditions and rare or non-existent jobs. Children were sent out very young to help feed the family, but many still couldn’t get by. Sometimes, when it got to be too much, parents might bring their children/child to a Home, like Dr. Barnardo’s Stepney Causeway. There, the child would be fed and well cared for, so these places probably saved many lives. However, the parents sometimes left their children only temporarily, planning to return for them in a few weeks, whenever they could get back on their feet. Oftentimes when they did return, the children were already gone, loaded onto a ship and sent to a faraway land without the parents having any idea at all. I tried to imagine what that might be like …

“Just a few weeks is all. I need maybe three, four weeks. Just ‘til I’ve my feet under me, right?”

“Her name?”

Don’t tell her, Mum.

But Mum leaned forward, said, “Clara. She’s Clara Mary McKinley,” and Clara’s tummy swirled like she was going to get sick. They both watched the woman’s pen scratch across the page.

“Age?”

“Well, she’s six. I know she’s small and all, but she’s six.”

“Mum?”

She felt her mother’s hand pat the top of her wool cap, the great prize she’d found in the rubbish that day. Mum didn’t look down. Her attention was on the woman behind the desk.

“You said you feed her here, aye?”

“Oh yes. She’ll be dressed and fed, and she’ll have lessons. There are lots of other little girls for her to make friends with. She’ll be well taken care of. You’re making a wise decision, Mrs. McKinley—”

“Miss. Miss Alice McKinley.”

“I see.” A black scribble was added to the paper on the desk. “And her father?”

“I’ve no idea.”

People always looked at Clara’s mum that way when she said she didn’t know Clara’s father. Like she’d just slapped them. Then they regarded Clara with the same kind of disdain as they would if she’d stepped in manure. Clara never understood why.

The woman’s smile was like a string pulled tight. “Well, as I say, you’re making a wise decision, leaving her with us. She’s much better off here while you get back on your feet.”

Food and clothes and all that sounded wonderful, but the woman’s squinty eyes made Clara want to run and hide. “Mum? I’ll be good. I’ll be quiet. I’ll stay out of your way. Lemme stay with you? Please, Mum?”

“Hush now.”

“I’ll help you, Mum. Please. I don’t want—”

She bent down so they were eye to eye. “Remember how we talked of it? You’s no help to your ol’ mum with no food in your belly, is you?” She straightened, agitated. “Right. What’s for me to do?”

“Nothing, dear. It’s all taken care of.” The woman in black rose, went around the desk and put herself between Clara and her mother. Her sleeve curled around Clara’s back. “We’ll take good care of her.”

Clara had hoped with all her hopes that this wouldn’t happen. It was only last night they’d talked about coming here, to this Home. Mum told her it would just be for a little while but didn’t matter if it was only a few hours, that was too long by far. Clara cried and cried, then Mum cried and cried, but in the end there was no choice. They were both hungry and cold, skinnier than spiders. Mum had done all she could to feed them, but it wasn’t enough. She had hugged Clara so tight she could scarcely breath, then she set her sharp chin on her head, told her she needed to be on her own, work day and night so she could give them what they both needed.

“For now you’s only under me feet,” she’d said.

“I won’t be. I’ll only do as you say, and I’ll be good—”

But all last night and all this morning Clara had thought maybe it’d be like on those rainy nights when the wind blew like as to take the walls with it, but it never happened. Never happened. Life had been hard, but all the scariest things had left them alone: the wind settled down as it always did, Clara woke up beside her mum as she always did. She’d thought this might be like that, too.

The woman patted Clara’s shoulder. “Say goodbye to your mother.”

Clara threw herself against her mother, arms wrapped tight around her legs, so mum squatted to hold her the right way. Clara dove into her familiar arms, burrowed her nose against her neck, wondered if she held on tight enough could she just go with her? Could they just forget all this?

“Mum! Mum, please!”

“Just a month or so, my girl,” she whispered into her ear. “Then I’ll bring you home, and it’ll be someplace warm where we have somethin’ to eat.” She gently but firmly pushed Clara away from her then stood straight. “You be good as gold for this lady, you hear? Good as gold. Right,” she said, addressing the woman again. “She’ll be good for you,” she told the woman, and Clara heard her voice shaking. “And I’ll be back in a few weeks.”

She was gone without another look, holding her hat against the rainy wind, gone like the sun after the door slammed shut.