- Subscribe to my newsletter! Click here →

Tommy Jr

Tommy Jr kept busy, and he gave us all a snapshot of what it might have been like for a young man to stay home while the others were out there, fighting and dying for freedom.

Tommy liked peace and quiet. His uncle said that made him a lot more like his mother than his father, and while he agreed with that assessment, sometimes he thought he’d rather be associated with his dad’s brave, almost arrogant spirit. The spirit the Atlantic had swept away a couple of years back.

Tommy liked peace and quiet. His uncle said that made him a lot more like his mother than his father, and while he agreed with that assessment, sometimes he thought he’d rather be associated with his dad’s brave, almost arrogant spirit. The spirit the Atlantic had swept away a couple of years back.

On the other hand, he was secretly very glad he was still a year too young to go to war. He didn’t want to even think about what that might be like. He’d heard enough from the letters his cousins sent home, and they’d only made him wish he could take off and hide in the woods.

Just because a war was roaring through most of the world, that didn’t mean life slowed down here on the shore—although everything was relative, of course. A lot of the local manpower had gone off to fight, but the world still needed to eat, and Uncle Danny never closed the plant if he didn’t have to. Winter storms or hurricanes might shut them down, but other than that they were almost always there, receiving salted fish from the local fishermen or bringing in supplies. Wartime was a lean time for everyone, and often the fishermen came off their boats and slumped into the fish plant, frozen and tired to the bone. Sometimes all they could do to help pay off their debts was bring in more fish then process them alongside the regular workers.

If Tommy and the others weren’t at the plant, they were driving to the railway station at Musquodoboit Harbour and either picking up twenty-five to thirty barrels of gasoline or unloading five hundred bags of salt, shipped in one hundred pound bags. And with gasoline at thirty-five cents a gallon, those trips were expensive. It was a good thing the gas rationing they’d put in place last April was only for personal consumption, otherwise the fishing industry would have come to a screeching halt. When it came time for Ed Burns or Mr Arnish to send out their own trucks from the city to pick up the crates of fish, Tommy and the others put their backs to it again, loading up those trucks.

When Tommy was finally done for the day, he’d head out to check his traplines, if the weather allowed. It was time consuming, but he sure made a lot of money that way. Rabbits, otters, muskrat, fox, and mink were what he usually caught. A mink was special. He’d get a pretty stack of pennies for that. The one time he got lucky enough to land a bobcat it was worth a whopping hundred and eighty dollars. Colin Bonn traveled around, buying up furs all along the shore, and he was a fair man.

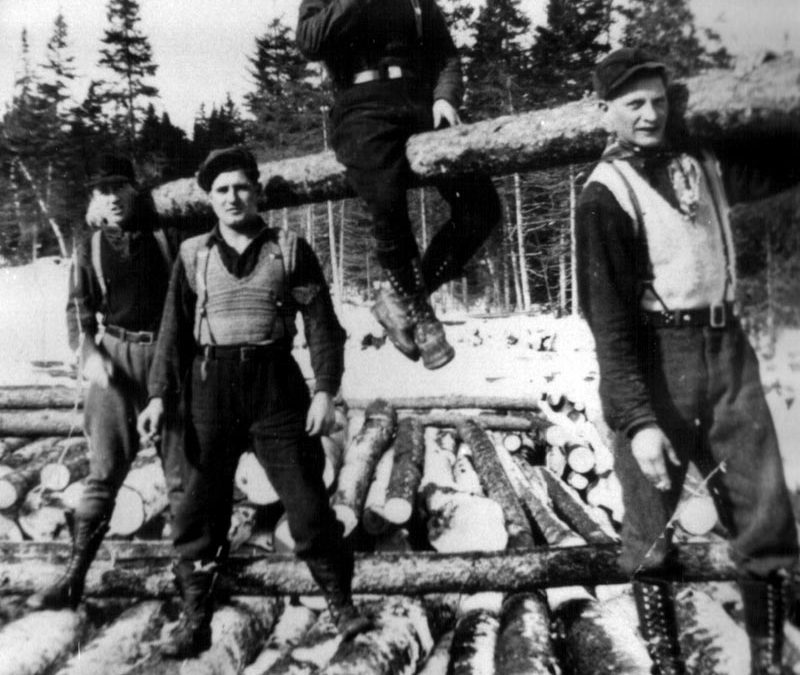

Despite the heavy lifting, Tommy was happy to have the job at the plant, when it came down to it. He wasn’t like some of the other boys who had to work for the pulp companies, slaving through nine-hour days for a dollar and a quarter, living at the camps, working for Byron Mitchell and his brother, Jock. Winters were tough, but the summers were worse. Tommy had done it for one year down in Guysborough County, and he’d decided he preferred the stink of fish to the sweet, cool, clear air in the woods if only because of the black flies. Those little demons would eat a man alive. Only way to survive was to mix up a can of pine tar and lard then smear it all over himself. Stunk to high heaven. Not even the flies wanted to get near him then.

Once the trees were cut, they river-drove the cut spruce, pine, and fir logs then loaded them onto barges. Those were big old boats, like the one Stewart Williams piloted, called the Liverpool Rover. She held eight hundred cords of wood and was so big it took her two or three hours just to turn around in the channel. Tommy’d stayed around a few times after he was done, watching the couple of dozen men who worked on her, picking out the wood with their poles, lining it all up for the chain to grab. From there the winch driver swung it around and down the hole, but that chain didn’t always hold tight, and the deck could get awfully slippery. Tommy’d seen some pretty horrible accidents in the lumber business. Lots of busted bones, lots of blood. He sure didn’t think the three dollars they got paid for loading a ship was worth it. The lumber headed down to the water-powered sawmill at Salmon River, owned by John Mitchell and his brother, Andrew, then the pulp was shipped down to Liverpool.

He was glad to get back to the fish plant after that summer working lumber, but those were long days, too. Hard days. Lately Tommy’d begun to fantasize about signing up with the Navy, or at least the Merchant Marine. He didn’t want to fight, but there were times he thought it might be easier than what they had to do here, day in and day out. Then again, every time he considered signing up he remembered Norman.

Ever since they’d gotten the telegram—a few months ago—nothing had been the same at home. Norman is dead. The family tried to move on, to face days the same way they used to, but there was less laughter now. People snapped more often, kept to themselves. Even Grace sank into bad moods, which was uncommon for her. Uncle Danny could get pretty dark at times, avoiding the rest of them with a purpose, and when that happened most of the family recognized his expression and stayed away. In the past Auntie Audrey had apologized on his behalf, tried to explain that the war had left him with some very unpleasant memories twenty years before, saying that sometimes they came back to haunt him. Auntie Audrey seemed busier than ever, but she wasn’t distracting herself with her paints like she normally did. When he asked her why not, she just smiled and explained that she hadn’t been able to see clearly for a while.

These days Tommy hadn’t had much in the way of concentration either. He found himself putting things in the wrong places, forgetting what he was doing. So when Uncle Danny had unexpectedly suggested he take a little time and set off hunting, Tommy had grabbed the opportunity and run with it. He hadn’t asked why, not in so many words, but his uncle had seen the question in his eyes.

“Once in a while a man needs to go off on his own, Tommy. Looks like you could use that right about now. Head to Abbiecombec. Bring back some meat for the rest of us.”

Didn’t seem to matter how old he was, his mother wanted to take care of him. This morning she bustled around, making sure his pack was full of food and he had everything he’d need to keep warm.

“That’s enough, Mom. I can feed myself, you know.”

“You can never have too much food, Tommy. Especially in the winter. You never know.”

“There’s blankets at the camp,” he reminded her.

“What if there’s a cold snap? What then? Grace said Mrs Gardner told her it was supposed to snow.”

Mrs Gardner told everybody everything. He swore that woman was part witch, with all her superstitious ideas. “Well, I do have the stove, you know. Loads of firewood, too. We stacked it fresh last time.”

He tried not to sound sarcastic, but sometimes she seemed to forget he was grown up. He was a practical person, had a good handle on the way things were and the way he needed them to be. He knew it was cold and the night would be freezing; it was January, after all. He was prepared, as always. Besides all the hunting equipment—both his guns with a full clip in the .303 British and an extra box of .22 shells in case the rabbits were out in force, a roll of snare wire for the rabbits, burlap gunny sacks and rope for hanging any meat he might land, the fishing line and hooks, and the bowie knife at his belt—he had matches, compass, tin cup, and whatever she’d packed for him to eat. When all was done, he figured he was pretty much carrying his own weight on his back.

“You have your long johns on?”

“Of course.”

“You’ll be back day after tomorrow, right?”

“Might stay a few more nights. Depends what I get. Don’t worry.”

She tugged the front of his coat together under his chin, smiling at him like she always had. “How can I not worry about you, Tommy?”

He closed his eyes when she leaned in to kiss his cheek. “Love you, Mom,” he said, turning to go.

After pulling on his heavy coat and boots, he tucked an extra pair of gloves in his pocket along with his jack knife, then he hung the heavy rucksack strap over one shoulder. The sling of his beat up old rifle scabbard slipped over the other, packed tight with the rifles and a couple of oily rags to keep them from rubbing. He stepped outside and the wind kissed his other cheek, but it wasn’t nearly as gentle as his mother had been. Tommy pulled his scarf up, covering his chin, then set off on the trail, already cut through the knee-deep snow.

The camp at Abbiecombec Lake was about an hour’s trek, partially along the hauling road. Though the day was cold, the squeaking crunch of his boots on the snow was a friendly sound, and sunlight twinkled like stars over the week-old blanket of snow. Its smooth surface was dotted by rabbit tracks, but Tommy decided he’d wait until he was a little closer to the camp before he caught his dinner. With this many it’d be easy to find them. At the sides of the trail the woods were dark with fat Balsam Fir and Red Spruce, perfect for sheltering deer, among other things. Chances were they’d be popular with grouse right about now. The lanky Tamaracks, having shed all their needles, were useless to the creatures this time of year, but come spring their branches would bounce under the weight of tiny warbling choirs.

Looked like today’s sunshine might be brief, just like Mrs. Gardner had foretold. A bank of menacing grey clouds was building ahead, coming in rather quickly. The sunrise that morning had been a bold red warning sign. Good thing there was a shovel at the camp; he would probably need it. At least the clouds should help bring up the temperature. He pulled off his mitts so he could tie his cap’s ear flaps under his chin. The woolen cap had a luxurious lining of rabbit fur, and when the flaps hugged his cold cheeks it felt almost decadent.

Sometimes it was easy for Tommy to get caught up in the beauty of the place, to allow himself to feel small and unimportant in the midst of all this. The wild, uncaring earth paid no attention to the ongoing disasters, the deaths and tragedies happening in the human world. The trees, grass, water, and animals simply grew, existed, did what they were supposed to do, then they died. There was a certain peace to acknowledging that. To knowing that this world around him didn’t feel the pain Tommy felt, didn’t miss it either. That his pain was so small, so remote among all this, it almost didn’t matter.

It helped for a little while, but the truth kept coming back at him.

Norman was dead. That shook Tommy hard. When he tried to picture his favourite cousin nowadays he could see nothing but a black hole.

Just like that the sunlight was snuffed out, and the first twisting, wandering snowflakes drifted down like shy little children curious about what they were getting themselves into. Beyond them floated millions more, and they appeared to gain both confidence and strength in their numbers. Tommy drew up his collar when they started tickling his nose, and he picked up his pace as well. At least he was heading into the heavier forest, avoiding most of the snow.

He loved the silence of a snowstorm—before the wind started up, anyway. With so much action swirling around him, the quiet seemed even more magical. He looked up, wondering how long this might last, but it was hard to tell. The only indication of the sun was a white glow from behind the clouds. If it didn’t pass over quickly, he’d have to rely on his backpack for supper. His mom would be happy to hear all her packing had been worthwhile.

The camp was about twenty minutes away—as long as the path didn’t get much worse. He shifted his backpack onto his other shoulder and pressed on.

But it did get worse, going from tranquil to tempest in the blink of an eye, and the forest path didn’t protect him. Turns out the early flakes were only scouts for the main army, and the full force rode in on a powerful, cutting gust. Everything around him bowed to the wind, including him, and concern sparked in Tommy’s chest. These kinds of storms were unpredictable. Could be gone in a minute, could shriek through the night. Only thing worse than wandering through one of these storms was being hit by one when they were out fishing. There was nothing colder than that.

He had to be getting close to the camp. It was hard to see much now since he was forced to squint against the storm. The gentle, tentative flakes hardened to tiny stinging bullets, and the wind kept reloading and firing hard. He kept his eyes on his feet most of the way, peeking up once in a while to check landmarks. Sometimes it looked a little different after time passed, but he was pretty sure he recognized the big oak out that way, the cluster of spruce to his left, bending almost double with the gale.

Except maybe he didn’t. He didn’t recall having to step over that old trunk before. He pressed on, fighting early tremors of panic. Where was the pile of rocks that said he was almost there? It should have been obvious even if it was drifted over. He should have been able to see it even through the wall of white that now surrounded him. He clambered over another unfamiliar lump in his path and slipped, landing hard on one knee, but he quickly righted himself. The knee throbbed, was going to leave a bruise, but he didn’t care. His knee was the farthest thing from his mind.

Where the hell was he?

The backpack caught on a branch and wouldn’t let go, so he slipped it off his shoulder to fix the problem. Frustrated, he yanked it loose and set it temporarily on the snow. Without its bulk he could twist around more easily, maybe figure out where he was. Except that didn’t help. Didn’t matter which way he turned, he could see nothing. Absolutely nothing. He was alone in the middle of the biggest snowstorm he’d ever seen, unable to tell if his next step would be into a tree or an open space. Made no sense to move blindly, except it made no sense to simply stay here, waiting to freeze to death.

The storm was far from silent now. It screamed through the trees, ferocious and hungry, ripping branches from trees. Tommy suddenly realized danger could fall from above as well, and he shuffled a little farther, having no idea if that would help him or not. He couldn’t help shouting out when the next gust came, bringing with it the ominous crackling and groaning of breaking branches. The force of it practically shoved him over, but he staggered upright and was just catching his breath when a massive tree crashed to the ground beside him.

That’s when he discovered where he was. The ice beneath his feet suddenly gave way, and he dropped like lead into the silent, icy waters of Lake Abbiecombec. Keep your head up! He kicked hard, scrambling for the surface gleaming vaguely overhead. He couldn’t think of the water he’d swallowed, couldn’t think of the ice already forming back in place over his head, couldn’t think of his limbs seizing up from the cold. No time. He grasped for the sky, reached for the storm, and finally burst through, screaming for air. The wind screamed back. Tommy clawed his mitts over the ice, hauling the dead weight of his body through the jagged hole. Pull, damn you, pull! The spinning, terrifying world brought his father’s voice to him, and he choked out a panicked sob. He was not going down like his dad. He was not.

His chest pulled free. He leaned farther, farther, inching away from the water … almost there! … but just as he wriggled his hips over the edge the terrible crackling sound came again and the ice shattered.

“No!” he gasped, managing to keep his head up. It was useless to yell but impossible not to. “No! God, no! Help!”

The screams stole his breath away, and he panted with exertion, searching for air.

“Help! Help!” But no one was out there. No one would hear.

Stars danced across his vision like the first snowflakes he’d seen that day. His boots felt like anchors, his hands were numb, but still he grasped at the slick surface. How long could he fight? Forever. He could fight forever if he had to. The edge of the water had to be close—he hadn’t been away from the trees for that long, had he? Three more times he fought back, and the last time he was free to his hips again, but the ice was too thin, his body clumsy and heavy. The surface crumbled and the water’s embrace tightened, holding him there.

The wind cut past him, racing over the ice to bend the trees on the opposite side of the lake, spinning snow behind it. The sky was nothing but white, dancing with more white, closing in on him from all sides. He was losing his grip, he could barely breathe, and the world moved more slowly both in and out of the water.

He couldn’t fight forever, he realized slowly. He couldn’t.

I’m sorry, Dad. I’m so, so sorry.