- Subscribe to my newsletter! Click here →

Camp X

Camp X was Canada’s top secret, paramilitary training school, the only one of its kind in North America. Prime Minister Winston Churchill and others in Britain’s SOE (Special Operations Executive), recognized early on that covert communication and solid intelligence were the only way they’d win the war, so Churchill directed the SOE to build something that would “set Europe ablaze”. That led to Camp X’s creation. There, they taught sabotage and subversion behind enemy lines, they recruited and trained resistance fighters, and they f

Camp X was Canada’s top secret, paramilitary training school, the only one of its kind in North America. Prime Minister Winston Churchill and others in Britain’s SOE (Special Operations Executive), recognized early on that covert communication and solid intelligence were the only way they’d win the war, so Churchill directed the SOE to build something that would “set Europe ablaze”. That led to Camp X’s creation. There, they taught sabotage and subversion behind enemy lines, they recruited and trained resistance fighters, and they f ound safe routes to help downed Allied pilots or escaped POWs get home. The camp’s vast 275 acres of land were close to Whitby, Ontario, fifty kilometres from the US, across a field from Lake Ontario. In addition to its classrooms and gymnasium, firing range and explosives field, Camp X came with a field of highly sensitive rhombic antennae and a parachute Jump Tower.

ound safe routes to help downed Allied pilots or escaped POWs get home. The camp’s vast 275 acres of land were close to Whitby, Ontario, fifty kilometres from the US, across a field from Lake Ontario. In addition to its classrooms and gymnasium, firing range and explosives field, Camp X came with a field of highly sensitive rhombic antennae and a parachute Jump Tower.

Since the very idea terrifies me, I’ll address that parachute Jump Tower first. From the base of a ninety-foot ladder, the trainee climbed to a shaky 4′ x 4′ platform that offered no railings for either balance or safety. Just staying upright would have been a challenge, since they would have been jostled by strong winds sweeping up those ninety feet from Lake Ontario. From the platform, the trainee grabbed a rope and swung down onto bales of hay provided by a local farmer. Once they hit the hay, their feet would drag until the momentum stopped, then they’d finally let go of the rope. According to the world’s expert on Camp X, Lynn-Philip Hodgson, students did this every day, over and over until they were a) no longer afraid of heights b) able to safely land and not break any bones.

Among many other things that you will read in my Acknowledgements, Lynn-Philip Hodgson was one of the writers for CBC’s excellent mini series, “X-Company”, which I highly recommend. On the website for the show is a story about a man named Gustave Biéler, an extraordinary, real life agent from Camp X. Gustave’s reputation went well beyond my idea of Gus, but I did enjoy thinking of him this way: “November 18th, 1942: The SOE deploys Gustave Biéler, a former Montrealer, into France. Despite injuring himself during his parachute landing, he goes on to organize countless missions to sabotage German supplies and logistics and is considered one of the SOE’s best agents. Biéler wreaks so much havoc that the Gestapo is forced to create a special team to track him down and capture him. Eventually, Biéler will be charged with the monumental task of helping to pave the way for the D-Day Invasion.” Unfortunately, Biéler was arrested by the Gestapo in Saint-Quentin, France in 1944. He was transferred to Gestapo headquarters, separated, and tortured, but he never broke. Eventually he was sent to Flossenbürg concentration camp and executed with an honour guard on September 5th, 1944.

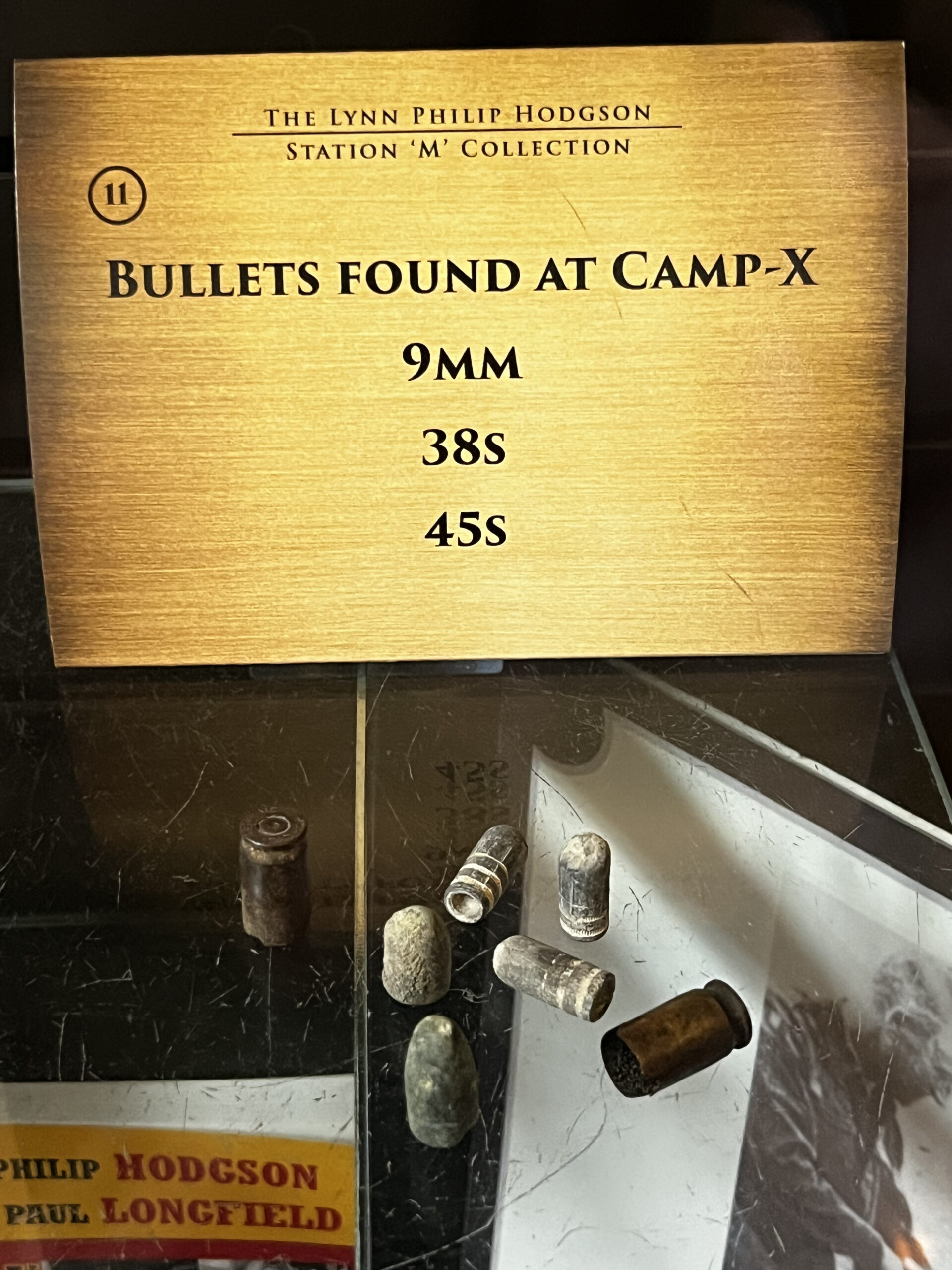

Over five hundred agents and instructors participated in Camp X’s programme, having faced up to fifty-two different courses during their training. They learned various kinds of ‘Unconventional Warfare’, including disguises, surveillance evasion, explosives and weapons training (in which only live ammunition was ever used), coding and ciphers, underwater demolition, the interrogation of prisoners, and much more. The most physical exercises, including self-defense, were extremely rigorous. Of the many men and women who trained at Camp X, probably the best known was author Ian Fleming, who went on to share some of what he’d learned in his James Bond novels. Other noteworthy attendees were screenplay writer Paul Dehn, and children’s author Roald Dahl.

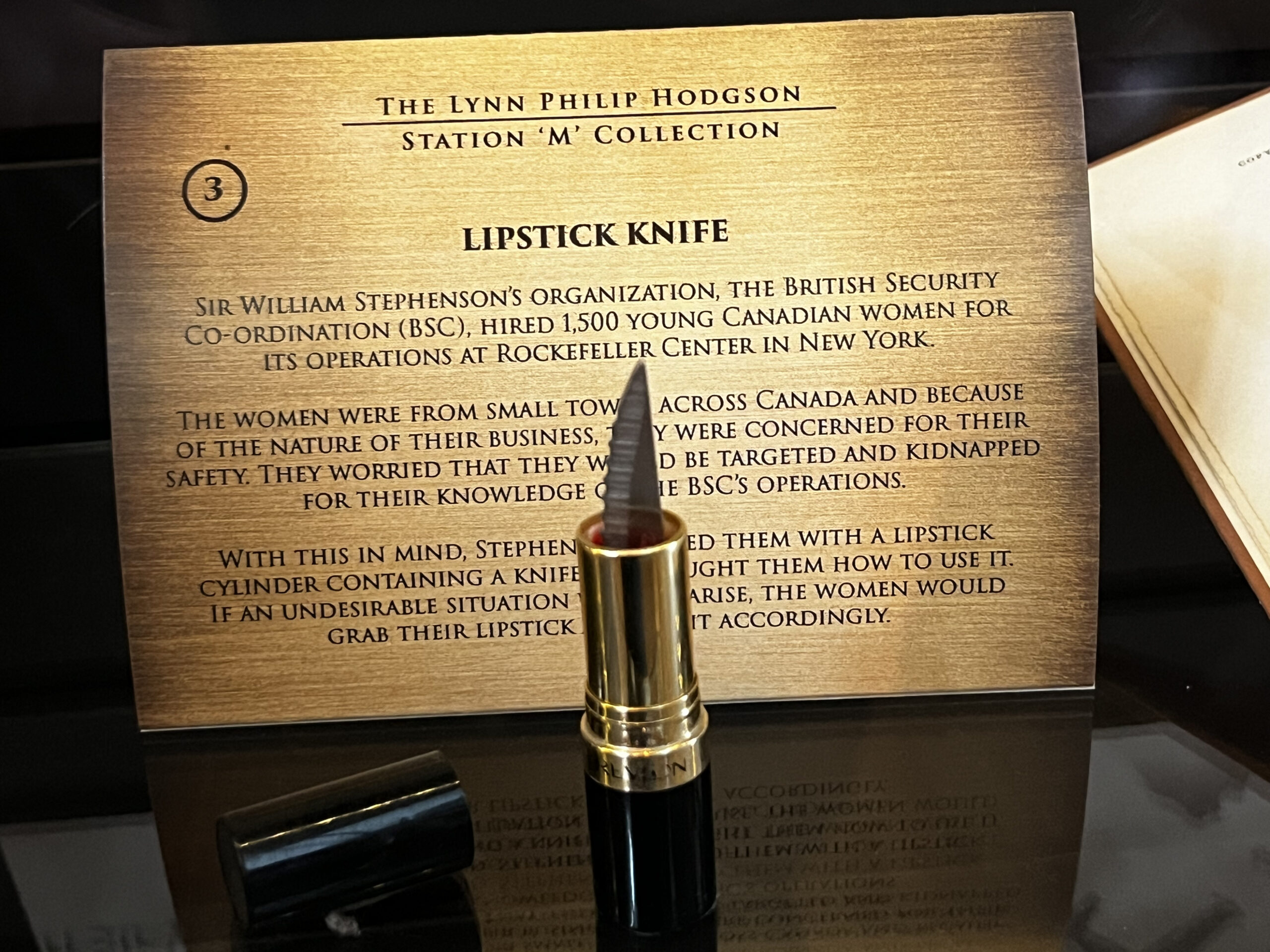

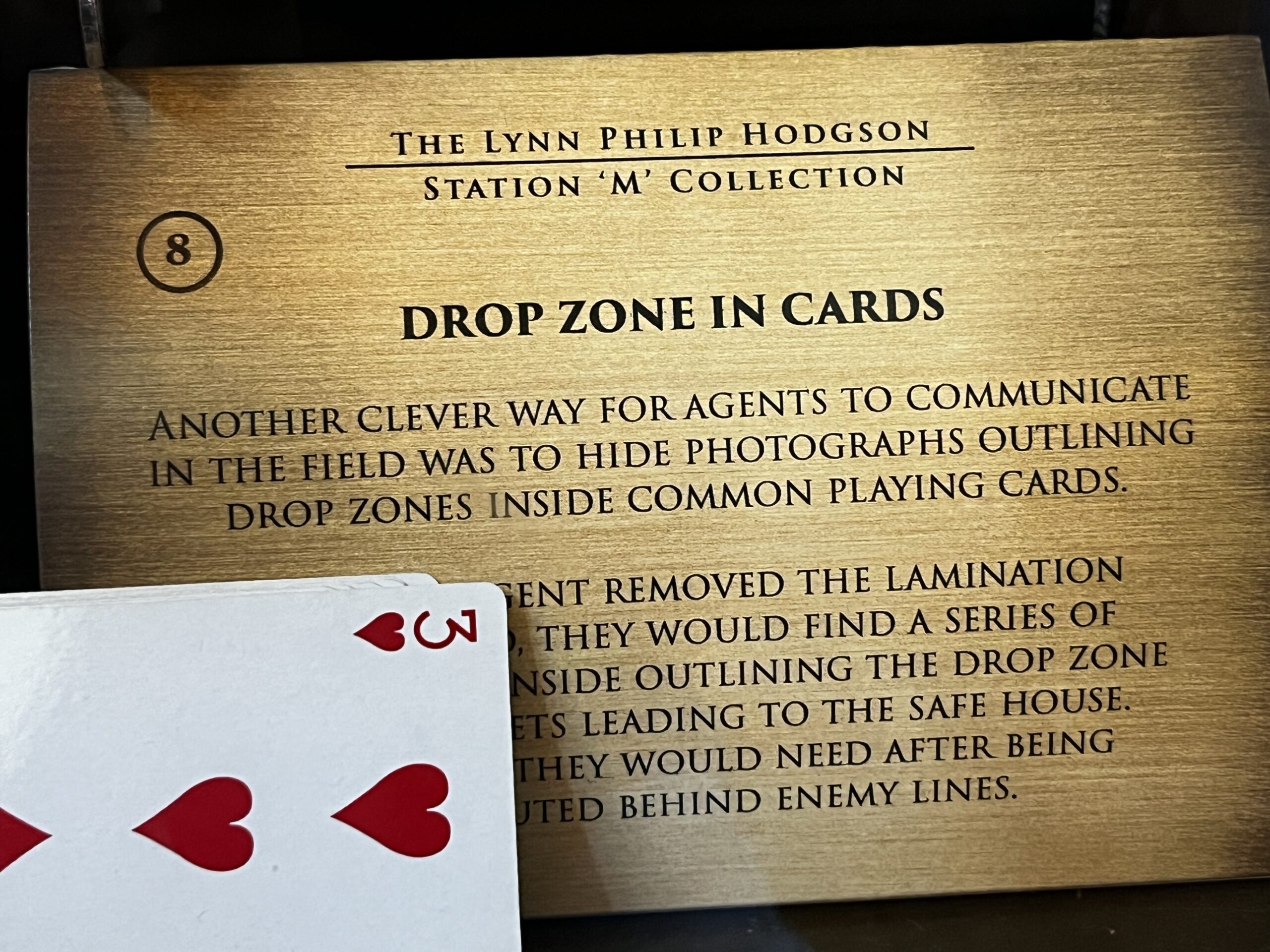

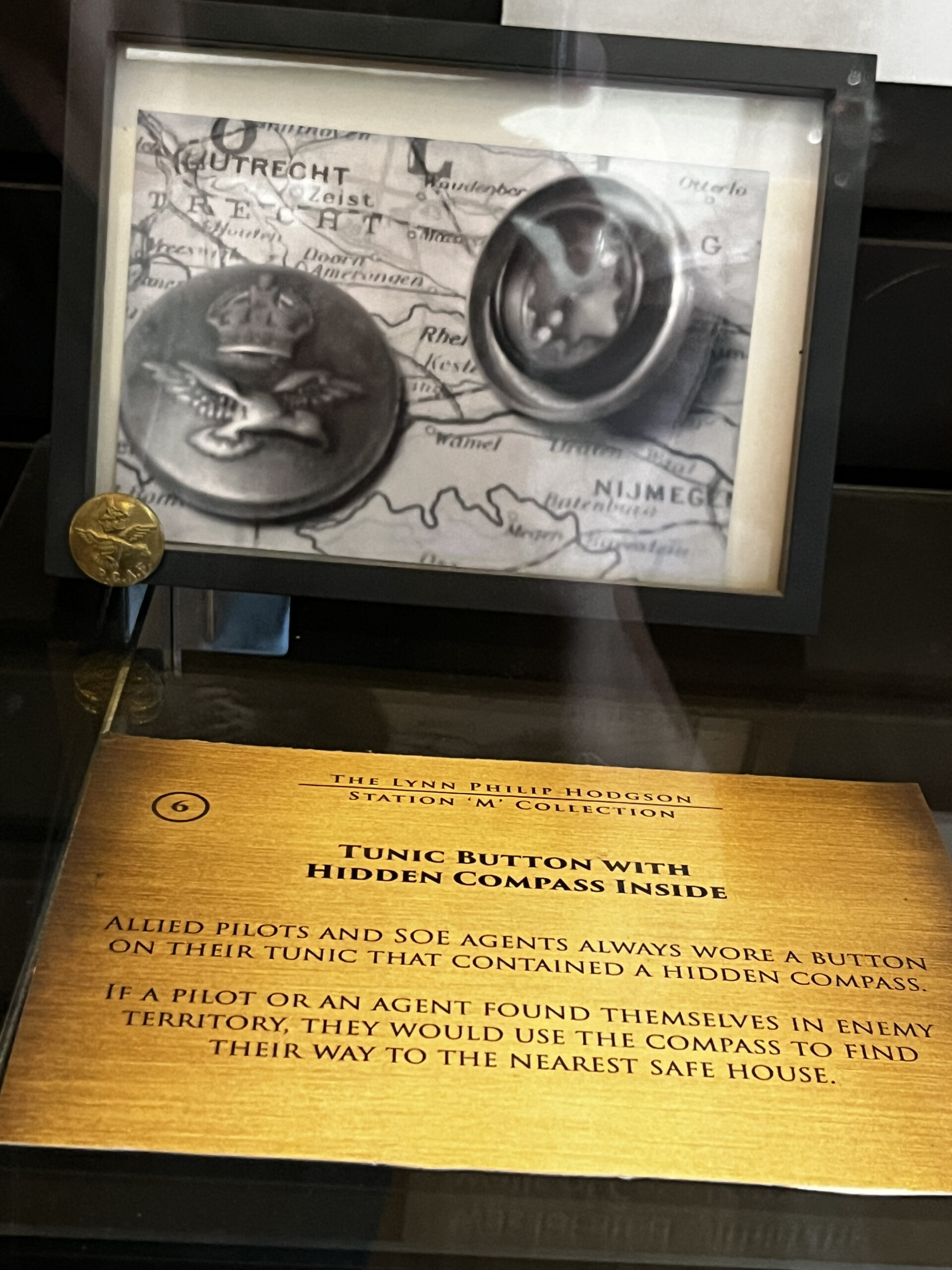

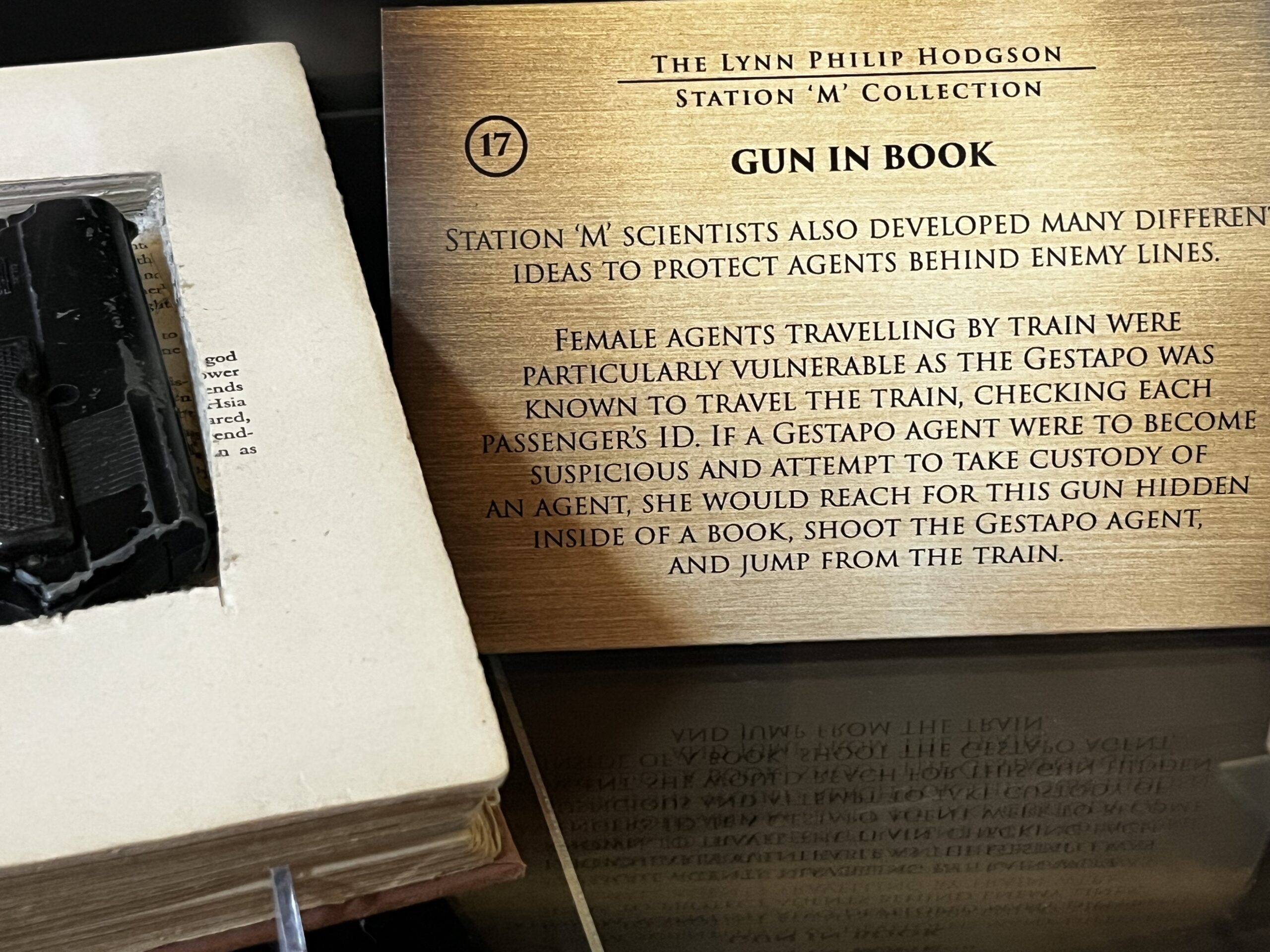

Here are just a few of the handy dandy little “James Bond” tools that “Station M”, part of Camp X, sent out with their operatives. I particularly like the Lipstick Knife!

After the war, the chief of the SOE declared that, “Per capita, the secret war was bloodier than the Somme. The only difference was that the cries were muffled and, in many instances, the corpses were never found.” Nor were most of the records, since the people in charge of Camp X celebrated the end of the war with a huge bonfire. After that, the only source of information available would be from actual interviews. Those would be extremely difficult to find, since every person there was still held to that oath of secrecy for the next four decades. Very few of those are on public record even after seventy years. Imagine the stories they could tell!

And then, as Dot would say with a fond sigh, there was Hydra, Camp X’s one of a kind, 15 mega hertz short wave transmitter/receiver responsible for sending and receiving Allied radio (including telegraph) signals around the world. Hydra was the most powerful telecommunications relay station of its kind, “handmade” after a few Canadian amateur radio enthusiasts sold the camp their apparatuses. It was connected to a huge rhombic array of antennae in the field to the south of the main building, and because of its reach and the topography of the land, Dot could reach Britain, other Commonwealth countries, and the United States while still keeping both coding and decoding information in relative safety from the prying ears of German radio observers. Communications officers like Dot were in direct communication with Bletchley Park. At the end of the war, Bletchley Park notified Camp X directly. Seventy years later, they held a reenactment of that moment (in Morse code). I have put a link to that video below.

Camp X continued to be in service at the start of the Cold War. If Hydra let them know that the Russians were listening, the agents happily played loud music over the system to block them. Hydra was terminated in 1969.